About the author

Matthew Knight

Matthew Knight is a Canadian ethnomusicologist (PhD U. Illinois Urbana-Champaign 2019) whose research focuses on the polyphonic vocal music of the Republic of Georgia. As part of his research, Knight lived for an extended period in the remote highland region of Svaneti with his family.

Svaneti’s culture is famed in Georgia for being archaic and harsh, with Upper Svaneti often described as a “living museum” that offers insights into the worldview and customs of ancient Georgia. Its villages were isolated for many centuries among some of the highest peaks in the Caucasus range, and they still contain many medieval stone towers built for defense against enemies—primarily other Svans, due to an exacting local moral code that mandated blood feud. Svanetian culture was clan-based, and extended families lived together with their livestock in large stone houses. Even in the 1930s, it was not uncommon for thirty or forty people to be residing in a single house, a site for intergenerational music transmission. Svanetian music, full of three-part parallel motion, close interval harmonies, non-tempered intonation, round dances, and a stolid vocal timbre, is said to mirror the landscape, and is regarded as ancient and weighty.

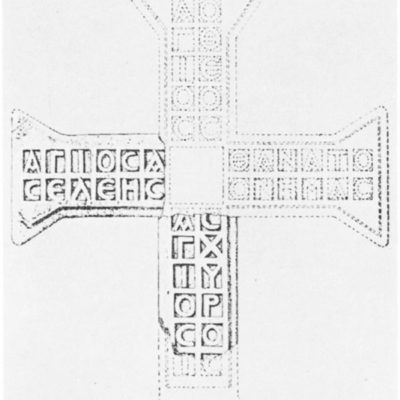

Due to its challenging highland topography, Svaneti was Christianized several centuries after most of lowland Georgia. Christianity became deep-rooted there, and by the 11th century, Svaneti was home to an icon-painting school and more than three hundred frescoed churches.

Nevertheless, Svanetian religion retained many aspects of animist practice, and the region is somewhat infamous for customs that are regarded as syncretic or pagan by the devoutly Orthodox. The situation was exacerbated by centuries in which there was little lowland ecclesiastical oversight. In the vacuum, paraliturgical practices developed that drew on the language and form of the Georgian Orthodox liturgy but altered it, sometimes significantly, to fit local understandings. Between the end of the medieval Georgian kingdom and the fall of the Soviet Union, the number of ordained Orthodox clergy in Svaneti was very low; some ritual responsibilities were handled by lay priests called bap, while other spiritual practices, primarily in the household, were led by women. The bap served as employees of the village, not the Orthodox Church, and could be removed by the elders if they performed unsatisfactorily. These religious specialists still exist, and even today, animal sacrifices or prayers to the sun are not uncommon. Notably though, most Svan practitioners see no conflict between their religious customs and Orthodoxy, and regard themselves as fully Christian. This distinguishes them from the followers of similar customs in neighboring Caucasus regions such as Abkhazia and Ossetia, where practitioners consider themselves to be pagans, not Christians.

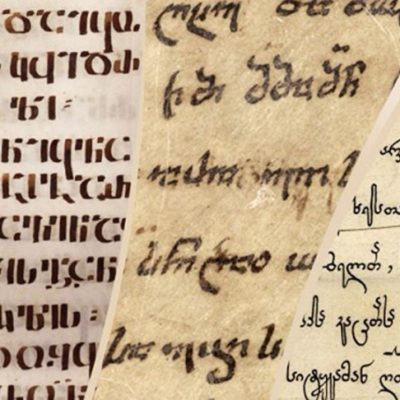

In a sense, Svan songs all bear the musical mark of pre-Christian ritual—the Georgian ethnomusicologist Dmitri Araqishvili stated “All Svan songs together… constitute a single enormous solemn and dark hymn to the gods and nature.” Some hymns, like Lile or Lazghvash, still contain largely animist texts, although many Svans today interpret them through a Christian lens; others like Kviria or Jgragish feature similar musical material sung to clearly Christian texts, suggesting that they may be re-texted versions of very old songs. There are also a few locally-composed chants meant to be sung during the Orthodox liturgy or during paraliturgical celebrations connected to the Orthodox calendar but celebrated by lay ministers outside of a church. A few song texts are impossible to reconcile with a Christian worldview, such as “Dala Kojas Khelghvazhale,” which describes a pre-Christian nature goddess giving birth on a mountain. However, such examples are relatively few.

The Lamproba festival is linked to the Orthodox liturgical calendar on the festival known as “Candlemas” in Western Christianity, but in Svaneti accompanied by syncretic customs relating to the fertility of the harvest.

Some Svan songs are secular—historical narrative ballads, songs praising famous heroes for their exploits, and entertainment songs—but they can not always be easily distinguished from sacred chants. It is often hard to determine the genre of a Svan song by its musical material. The hymns held to be the most ancient, like Lile or Kviria, tend to be unmetered and slow. However, some of these hymns also exist in metered form, and can be performed as a round dance. One ethnomusicological theory holds that originally all songs in Svaneti would have been performed with a round dance, a very important ritual form in the region, pointing back to the inherently religious nature of Svan music.

In general, the musical language of Svan chants is quite different from that of lowland liturgical chant. It hews very closely to the usual system of Svan folk music: three-part chords in close harmony, frequently spanning no more than a fifth between outer voices; parallel motion and a preponderance of 1-4-5 “suspended” chords; largely stepwise melodies unfolding within a very narrow range; and a closing unison rather than a fifth. Further, many of these songs were created for ritual contexts that were primarily outdoors, requiring a very robust vocal quality rather than a more subtle approach appropriate to singing inside a resonant cathedral.

Svanetian hymns and round dance songs make a powerful impression upon many listeners, and for this reason they are favorites of many folk revival groups throughout Georgia. They have also earned significant interest from ethnomusicologists and folklorists. In the past two and a half decades, they have even captured the hearts of many foreign students of Georgian song, who prize them for their archaic nature, spiritual solemnity, and robust dissonant chords. Interestingly, foreign students of Svan music are often drawn to the pagan aspects of the hymns, although this is something most Svans downplay. Foreigners also often find that the parallel block harmonic motion and relaxed tempos allow them to experiment more successfully with Georgian intonation systems than the quicker, more contrapuntal songs characteristic of other parts of Georgia.

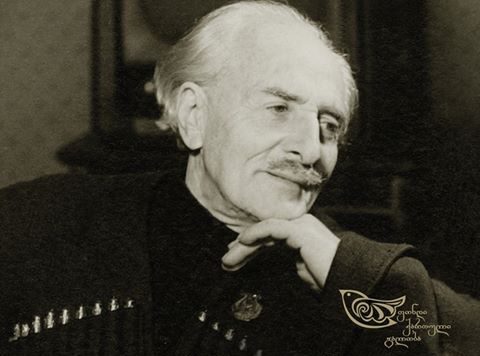

Like most of these foreigners, I had the great privilege of studying Svan music from the choir director and songmaster Islam Pilpani of the town of Lenjeri (1934–2017). Islam was highly respected in the folk music community for his knowledge of Svan songs, as well as his mastery of the Svan bowed string instrument called the ch’unir. I was particularly lucky to spend the summers of 2015 and 2016, as well as the intervening winter, in Svaneti, much of the time living at Islam’s house. During these months, and on other shorter visits, he taught me most of the local repertoire he knew—about 40 songs in all three voice parts, with the accompaniment of the ch’unir and chaeng (Svan harp) where appropriate. Besides Islam and his family, I also studied with singers in the Upper Svaneti communities of Etseri, Latali, and Mestia, particularly befriending the Chamgeliani family of Lakhushdi village. It was a deep honor to attend numerous religious festivals and funerals, where I got to experience Svan sacred chants and laments in person. While I make no claim to authoritative inside knowledge, I write about this repertoire with deep respect and affection, recognizing the power it continues to hold over practitioners and listeners.

* * * * *

See another article by Matthew Knight on GeorgianChant.org here: Kviria – Svan Ritual Chant

Article published in MUSICultures (2019): Folk Polyphony Goes Viral: Televised Singing Competitions and the Play of Authenticity in the Republic of Georgia

Recommended Reading:

Akhobadze, Vladimer. Kartuli (svanuri) khalkhuri simgherebis k’rebuli (Collection of Georgian (Svan) Folk Songs) (in Georgian). Tbilisi: T’eknik’a da Shroma, 1957.

Araqishvili, Dimitri. 2010. “Svan Folk Song.” In Echoes from Georgia: Seventeen Arguments on Georgian Polyphony, edited by Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Joseph Jordania, translated by Ariane Chanturia, 35–56. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Bærug, Richard, and Shako Margian. 2016. Europe’s Unknown Fairytale Land: Around Svaneti – On Foot and On Skis. Translated by Bjørn Giertsen. Tbilisi: Bakur Sulakauri.

Bolle-Zemp, Sylvie. Liner Notes to Georgie: Polyphonies de Svanetie. Translated by Peter Crowe. Le Chant Du Monde, LDX 274 990. Paris: Collection Musee de l’Homme, 1994.

Bray, Madge. 2011. “Echoes of the Ancestors: Life, Death and Transition in Upper Svaneti.” Caduceus 81:6–9.

Freedman, Sydney Walker. 2014. “The Logoi of Song: Chant as Embodiment of Theology in Orthodox Christian Prayer and Worship.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Limerick. https://ulir.ul.ie/handle/10344/4274.

Grigolia, Alexander. 1939. “Custom and Justice in the Caucasus: The Georgian Highlanders.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Kalandadze-Makharadze, Nino. “The Funeral Zari in Traditional Male Polyphony.” In Second International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony (2004) Proceedings, edited by Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Jordania, Joseph, translated by Marina Kubaneishvili, 166–78. Tbilisi: Tbilisi State Conservatoire, 2005.

Khardziani, Maka. “Formation of Three-Part Singing and Determination of the Type of Polyphony in Svanetian Traditional Music.” In First International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony (2002) Proceedings, edited by Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Jordania, Joseph, translated by Marina Kubaneishvili, 330–34. Tbilisi: Tbilisi State Conservatoire, 2003.

———. “Reflection of the Tradition of Hunting in Svan Musical Folklore.” In Second International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony (2004) Proceedings, translated by Liana Gabechava, 205–8. Tbilisi, 2004.

———. “Svan Hunting Songs.” In Fourth International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony (2008) Proceedings, edited by Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Jordania, Joseph, 222–27. Tbilisi: Ministry of Culture, Monument Protection and Sports of Georgia/Tbilisi State Conservatoire, 2010.

———. “On the Change of Three-Part Songs into One-Part Songs in Georgian Traditional Music (Racha and Svaneti).” In Fifth International Symposium on Traditional Polyphony (2010) Proceedings, edited by Rusudan Tsurtsumia and Jordania, Joseph, translated by Liana Gabechava, 168–72. Tbilisi: Ministry of Culture and Monument Protection of Georgia/Tbilisi State Conservatoire, 2012.

———. “In Memory of Islam Pilpani.” The V. Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire International Research Center for Traditional Polyphony Bulletin, no. 21 (June 2017): 5–6.

———. ed. Svanuri Khalkhuri Simgherebi – Svan Folk Songs: Collection of Sheet Music with Two CDs for Self-Study (in Georgian and English). Teach Yourself Georgian Folk Songs. Tbilisi: Georgian Chant Foundation, 2017.

———. Islam Pilpani (in Georgian). Kartuli Simgheris Moamage (Caretakers of Georgian Song) 5. Tbilisi: Kartuli Galobis Pondi (Georgian Chanting Foundation), 2019.

———. “Svaneti.” In Georgia: History, Culture, Ethnography, edited by Anzor Erkomaishvili, 2:192–202. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2019.

Knight, Matthew E. “Song Hunters in Svaneti: Musical Tourism and Other Intercultural Encounters in Highland Georgia.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 2019.

Mzhavanadze, Nana, and Madona Chamgeliani. “On the Problem of Asemantic Texts of Svan Songs.” Kadmos 7, no. 8 (2015): 49–109.

Nasmyth, Peter. 2006. Georgia: In the Mountains of Poetry. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

Topchishvili, Roland. 2009. Svaneti and Its Inhabitants (Ethno-Historical Studies). Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Institute of History and Ethnology. https://histinstitute.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/georgian_mountein_regions.pdf.

Tuite, Kevin. 1994. “The Svans.” In The Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume VI: Russia and Eurasia/China, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 343–47. Boston: G.K. Hall.

———. 1996. “Highland Georgian Paganism — Archaism or Innovation?,” Review of Zurab K’ik’nadze: Kartuli Mitologia, I, Jvari Da Saq’mo.” Annual of the Society for the Study of Caucasia 7:79–91.

———. 2002. “Real and Imagined Feudalism in Highland Georgia.” Amirani 7:25–43.

———. 2003. Violet on the Mountain: An Anthology of Georgian Folk Poetry. Translated and edited by Kevin Tuite. Tbilisi: Amirani.

———. 2004a. “Hunter, Shaman, Oracle, Priest: An Ethnohistorical Overview of Inspirational Practices in Highland Georgia.”

———. 2004b. “Lightning, Sacrifice and Possession in the Traditional Religions of the Caucasus, Part II.” Anthropos 99:481–97.

———. 2006. “The Meaning of Dael: Symbolic and Spatial Associations of the South Caucasian Goddess of Game Animals.” In Language, Culture and the Individual: A Tribute to Paul Friedrich, edited by Catherine O’Neil, Mary Scoggin, and Kevin Tuite, 165–88. Munich: Lincom Europa.

———. 2015. “The Semiotics and Poetics of South Caucasian Nonsense Vocabulary.” Unpublished draft. https://www.academia.edu/14281564/THE_SEMIOTICS_AND_POETICS_OF_SOUTH_CAUCASIAN_NONSENSE_VOCABULARY.

———. 2017. “St George in the Caucasus: Politics, Gender, Mobility.” In Sakralität Und Mobilität in Südosteuropa Und Im Kaukasus, edited by Thede Kahl and Tsypylma Darieva, 19–53. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. https://www.academia.edu/17881597/St_George_in_the_Caucasus_politics_gender_mobility.

———. “The Affordances of Orthodox Christianity for Georgian Vernacular Religion.” Presented at Central Eurasian Studies Society, 2018. https://www.academia.edu/38257748/Tuite_2019_THE_AFFORDANCES_OF_ORTHODOXY_FOR_VERNACULAR_RELIGION_sketch_pdf.

Virsaladze, Elene. 2016. Georgian Folk Traditions and Legends (Caucasus). Translated by David G. Hunt. Tbilisi: Artanuji.

Voell, Stéphane. 2013. “Oath of Memory: The Taking of Oaths on Icons in Svan Villages of Southern Georgia.” Iran and the Caucasus 17(2):153–69. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20130203.

———. 2015. “Moral Breakdown among the Georgian Svans: A Car Accident Mediated between Traditional and State Law.” https://www.academia.edu/9321227/Moral_Breakdown_among_the_Georgian_Svans_A_Car_Accident_between_Traditional_and_State_Law_2015_.

Zemp, Hugo. 2007. Funeral Chants from the Georgian Caucasus. Ethnographic documentary. Documentary Education Resources.

Kevin Tuite

Thank you Matt for this wonderful, informative article! I have just a couple of comments: First, I would hesitate to apply the word “animist” to Svanetian vernacular religious practices. This term has acquired a lot of the same negative, primitivizing connotations that “pagan” has, and in its strict sense, animism doesn’t really apply to the traditional Svanetian belief system. Second, I suggest you add the work of Nino Tserediani to your bibliography. She is probably today’s leading expert on Svanetian vernacular religion, and her two-volume book on the annual cycle of feastdays is an invaluable resource for understanding the contexts in which much of the musical repertoire is performed.

Matt Knight

Thank you, Kevin, for your comments! I will certainly make those adjustments in any future publications. Your expertise is much appreciated!