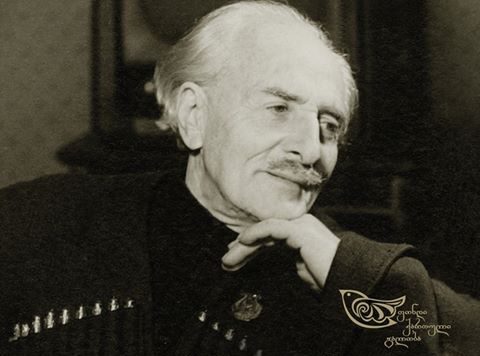

About the author

Matthew Knight

Matthew Knight is a Canadian ethnomusicologist (PhD U. Illinois Urbana-Champaign 2019) whose research focuses on the polyphonic vocal music of the Republic of Georgia. As part of his research, Knight lived for an extended period in the remote highland region of Svaneti with his family.

One of the most important and historically layered Svan ritual songs is the hymn Kviria. Like many hymns passed down orally over the centuries, Kviria exists in multiple variants. However, some of these variations differ to the point that it is almost impossible to imagine a common origin. According to Svan ethnologist Madona Chamgeliani, part of the reason for this divergence is that Kviria hymns are sung for two unrelated reasons. Perhaps two different pre-existing animist hymns were repurposed with similar titles.

In this article, I will primarily be discussing the “funeral Kviria,” which I learned from the late songmaster Islam Pilpani of Upper Svaneti. This version is distinct from a “ritual Kviria” that can be sung at the many religious festival days celebrated in Svaneti. The main connection between the funeral and ritual Kviria performance contexts is the theme of fertility.

Text

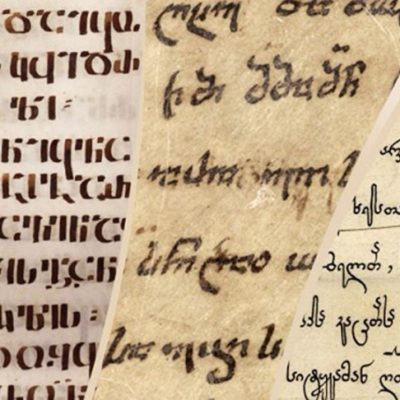

Whereas some Svan chants, such as the well-known Lile, contain archaic words that are now hard to translate, the funeral Kviria variant’s text is almost solely comprised of vowel sounds and vocables (singing syllables that lack lexical meaning but sometimes possess spiritual or magical significance).

Kviria lese da ho kviria

O, ubri yo, ubri yo, ubri hai hai yo, yo yo

Uwo, yi ha, ha yi ha, wu yi hai hai yo, wu yi wo ya ha,

Yi woi, woi, wo ya ha

Uwo, sa yi ha, wu yi ha, wu yi hai hai yo,

Wu yi, woi ho yo

Ha yi wa, wu yi woi ho yo,

Wu yi wo yi wo

The only text that scholars suppose to have lexical meaning is the first line “kviria lese,” believed to derive from the Greek “kyrie eleison” or “Lord have mercy,” a foundational component of the Christian liturgy. Transformations of this phrase appear elsewhere in Svanetian folk music and custom (“kiria wo lesia” in the hymn “Elia Lrde,” or the responsorial “sirian kvirian!” shouted during the door-to-door Likuriel festival).

Recording

A common (though not universal) tendency of unaccompanied Svan chants is that the pitch rises gradually as energy builds. While I have transcribed this performance with a modal center on A for ease of reading, Riho’s performance actually starts centered around A flat and ends close to B natural—a rise of a minor third. I have chosen not to attempt to indicate this rise, which should be conceptualized not as a key change but as an energetic bubbling up of musical excitement, accompanied by increasing volume.

A further caveat: the rhythmic values are only approximate, as Riho’s singers frequently push or relax the pulse. This transcription represents a single performance of Kviria, and numerous elements will differ slightly with each rendition, even if exactly the same singers are involved. However, I chose this version to transcribe because it is very close to the way I learned it from Islam Pilpani twenty years after the recording was made, indicating that there is clearly an enduring musical and textual frame.

Chant Analysis

The included transcription of a performance of the funeral Kviria by Mestia’s Riho Ensemble illustrates many features typical of Svan chant. However, it also illustrates the foibles of European musical notation when it comes to representing oral musics. It would be an unfortunate mistake to study the score alone without referring to the recording for intonation, timbre, articulation, and general matters of style (Download full Kviria transcription.)

In the middle of bar 15 I made a considered editorial alteration, beginning the “u wo” solo call in the middle voice a major sixth above “ha.” In this recording, the soloist—Geronti Pilpani, Islam’s cousin—begins “u wo” closer to a fifth above “ha.” However, when Islam taught Kviria and whenever I have heard members of Riho sing it, including in other recordings with the same soloist, this note has been a sixth. I suspect that the soloist sensed the pitch was already rising too quickly and entered on a lower note as a correction, whether this was a deliberate musical choice or spurred by body memory, I cannot say.

As with all Svan songs, Kviria’s intonation is decidedly non-tempered. When triads appear, they are somewhere in between major and minor, though they may lean in one direction or the other.

For example, in bar 2 I have written the choir’s initial chord as a major triad. However, when Islam taught Kviria, he sometimes sang the chord closer to a minor triad. Similar debatable triads occur in bars 4, 5, 6, and throughout the score.

Glissandos are frequent, especially when moving to a lower pitch. In the score, many of them are indicated with a short curved line, as before the second note of bar 2 in the top two voices. In most cases, these glissandos are short and occur immediately before the lower note. Short curved lines at the ends of phrases indicate a short collective fall off from the end pitch, which helps to punctuate the pause.

The singing is slow and relatively non-metrical, as indicated by the differing lengths of “bars,” which simply indicate phrases. The texture occasionally slips into two parts—for example, see bars 13–15, where the middle voice joins the basses in unison. There are also frequent melodic and harmonic fourths, both of which appear in the second and third chords of bar 3 from the top voice, and in bars 8 and 9 from the middle voice.

To Georgian scholars, all of these musical factors imply that Kviria’s music is indeed very ancient. The general texture, slow tempo, solemn mood, lack of pulse, and dearth of consonants make Kviria reminiscent of the zar, the wordless, polyphonic Svan funeral lament. The connection goes further than musical sounds, since this Kviria is also sung at funerals. However, it can only be sung for a person whose life was fruitful—they died at an advanced age, produced children, and were not predeceased by any of their descendants. This restriction is probably due to Kviria’s association with fertility.

Despite the Christian influence implied by “kviria lesa,” Kviria’s musical content and the majority of its text suggest pre-Christian origins. Some scholars describe a connection with an animist deity also called Kviria. Importantly, while the old Georgian animist religion included a god named Kviria who was later associated with Christ (as the Supreme God’s majordomo or second-in-command), according to folklorist Nino Ghambashidze the Svanetian Kviria was stronger and sometimes considered the supreme deity himself, responsible for weather and the revival of nature.

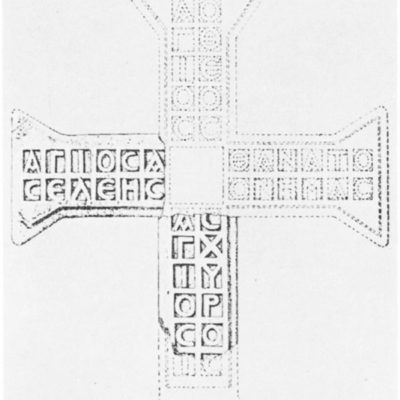

In the Christian era, Kviria has also become linked to the Orthodox St. Kvirike (St. Quricius/Cyricus). The similarity between the words Kviria and Kvirike may not be accidental, but cannot be speculated upon further here.

In Svaneti and other parts of the Orthodox world, St. Kvirike is associated with infancy—and fertility by extension—probably because he was martyred as a baby along with his mother.

His feast day (Kvirikoba/Lagurka) is celebrated on July 28 at Kala’s St. Kvirike Church, Upper Svaneti’s most important house of worship. The church is the home to a miraculous icon brought from the Holy Land, and oaths taken on this icon are considered the most serious and binding.

Kvirikoba is an occasion for pilgrims from all corners of Svaneti to make offerings, and has traditionally been an opportunity to pray for the birth of a child, especially a son.

The “ritual Kviria” song variant is sung at the festival of Kvirikoba and during other ceremonial occasions. Svanetian ritual festivals featured a cycle of seven hymns for different religious figures, including the Supreme God (the Christian God the Father), the Chief Archangel, and St. George. The Kviria sung during this cycle evidently honors St. Kvirike/Kviria.

While the funeral version of Kviria has been popularized in performances and recordings by groups like Mestia’s ensemble “Riho” or Dmanisi’s “Shgarida,” other versions of Kviria have been recorded by the Rustavi Ensemble or Tbilisi’s young Svan male choir, Kviria ensemble. Beyond these professional renditions, though, both Kviria variants, united by the concept of fertility, remain an important part of Svanetian ritual practice today.

* * * * *

See another article by Matthew Knight on GeorgianChant.org here: Introduction to Svanetian Chant

Article published in MUSICultures (2019): Folk Polyphony Goes Viral: Televised Singing Competitions and the Play of Authenticity in the Republic of Georgia

Svanetian Chant: Introduction - Georgian Chant

[…] Matthew Knight #molongui-disabled-link Kviria – Svan para-liturgical hymn […]